At Lee Abbey and New Wine this summer, I have been leading a series of sessions on ‘Gods of Our Age’. (I did the teaching myself last week; this week I am hosting a series of contributors.) It struck me some time ago that the gods of the ancient world were not merely the equivalent of our soap operas (though they might have functioned like that to some extent). Rather, they expressed the hopes, fears, aspirations and anxieties of people within those societies—often offering a way of dealing with powerful forces, both within and without, in a way which made them manageable. The first was on Mammon, the god of wealth, money and possessions. This second is on Mars, the god of war and conflict.

Mars in the ancient world

Mars in the ancient world

Roman Mars (the equivalent of the Greek Ares) was god of war and farming. Combining two aspects of life into one god was not uncommon, and for the men in any society, it was common to be farmers in the key seasons of sowing and soldiers in the season for fighting. (If you went to war in the seasons for sowing crops, you effectively made war against yourself. For ancient common on the spring as the time for making war, see 2 Samuel 11.1.)

Mars as original marginal to Roman identity, but gradually became absolutely central. The Wikipedia entry on Mars notes:

Mars was a part of the Archaic Triad along with Jupiter and Quirinus, the latter of whom as a guardian of the Roman people had no Greek equivalent. Mars’ altar in the Campus Martius, the area of Rome that took its name from him, was supposed to have been dedicated by Numa, the peace-loving semi-legendary second king of Rome. Although the center of Mars’ worship was originally located outside the sacred boundary of Rome (pomerium), Augustus made the god a renewed focus of Roman religion by establishing the Temple of Mars Ultor in his new forum.

Within the founding myths of Rome, Mars became the father of Romulus and Remus, the brothers who established the city.

It is striking that the Romans had a very different view of Mars from the Greek view of Ares:

But the character and dignity of Mars differed in fundamental ways from that of his Greek counterpart, who is often treated with contempt and revulsion in Greek literature…Although Ares was viewed primarily as a destructive and destabilizing force, Mars represented military power as a way to secure peace, and was a father (pater) of the Roman people.

This destructive and destabilising force became for Rome the way it secured its peace, its pax Romana—though I daresay that the nations who were conquered by Rome would have views Mars in a more Greek way than Roman.

The symbol for Mars was its spear, and Mars was so deeply associated with masculinity that our modern symbol for ‘male’ (a circle with an arrow) derives from Mars and his spear, and is the astrological symbol for the planet Mars.

Mars in the Modern World

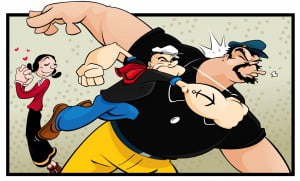

Western culture seems to be deeply committed to violence as the way of resolving differences and conflict. How does Popeye rescue Olive Oyl from the power of Bluto? By eating spinach which then allows him to win by force. How does James Bond defeat the global conspiracy of his enemies? With the help of intelligence and gadgets from Q—but in the end by brute force. We are deeply committed to conflict as the thing which creates narrative tension from the biggest budget film to the most popular TV soap opera. There is a constant correlation between might and right.

Western culture seems to be deeply committed to violence as the way of resolving differences and conflict. How does Popeye rescue Olive Oyl from the power of Bluto? By eating spinach which then allows him to win by force. How does James Bond defeat the global conspiracy of his enemies? With the help of intelligence and gadgets from Q—but in the end by brute force. We are deeply committed to conflict as the thing which creates narrative tension from the biggest budget film to the most popular TV soap opera. There is a constant correlation between might and right.

But conflict has a central place in other aspects of Western culture too. In the UK and US, the system of justice is adversarial rather than inquisitorial, and probably derived from the mediaeval practice of trial by combat.

The application of a market model in healthcare and education has put hospitals and schools in competition with each other for patients and students respectively. The school for which I was a governor had to become an academy because other schools around were doing so, and they were our competitive rivals.

At the 100th anniversary of the start of WWI we have been recalling the devastating destructive power of war. But this is no new thing. Genghis Khan‘s onslaught in the 13th century was so destructive that it is possible today to measure the ecological impact as whole tracts of farming land fell into disuse and went back to wilderness. He slaughtered 40 million people—one tenth of the entire world’s population at the time. Chinese census data from the time record the loss of 11 million Chinese lives. (He also encouraged religious freedom, and sired so many children that, today, 0.5% of the global population can trace their direct ancestry to him.)

The Thirty Year’s War in the 17th century was Europe’s longest and most destructive war. Parts of modern-day Germany lost 70% of their population. War is extraordinarily destructive of human life, resources and culture.

There is a fascinating episode at the end of the second Sherlock Holmes film with Robert Downey Junior Sherlock Holmes: a Game of Shadows. Holmes is trying to prevent his nemesis Moriarty from provoking war between the great powers. But Moriarty counters him: even if he succeeds now, war will come, since men are addicted to conflict.

Alan Storkey has argued cogently that armed conflict is inevitable as long as there is an arms industry who have a vested interest in seeing their products sold and used. Here we see the meeting point between Mars and Mammon—in the States named as the military industrial complex.

What Scripture has to say

One of the contemporary challenges of our age in relation to violence and religion is to ask whether ‘X is a religion of peace.’ This has mostly been claimed in relation to Islam, but it is a pertinent question for Christians too. There is plenty of violence in the Old Testament, and this causes (or should cause) problems for Christians. (On this, see Philip Jenson’s excellent Grove booklet The Problem of War in the Old Testament.) And yet there is, through the OT, glimpses of a vision of global peace and the end of warfare: ‘Nation will no longer war against nation…’ (Isaiah 2.4).

There are three key passages in the New Testament which have a bearing on this

- Jesus’ apparently pacifist teaching in Matt 5 ‘blessed are the peacemakers… you shall not resist the evil person, but turn the other cheek…’

- Paul’s language in Romans 13 on our obligation to ‘obey the powers that be’

- The alternative vision in Revelation 13 of state forces as agents of Satan ‘do not follow the beast’

It is interesting to note that, as far as we can tell, all Christians were pacifist until the early fourth century and Constantine’s dream from God that ‘Under this sign [of the cross] you will conquer…’

Christians have tried to resolve the tensions in these perspectives by means of Just War theory—that war should only be prosecuted by a just authority, with a just cause, to attain likely success, by just means, and when there is no other option.

But there is a further issue to be considered. I have argued elsewhere that reconciliation is a central idea in the NT’s understanding of what God has done in Christ for us and for all humanity. If reconciliation is of central importance in understanding what God has done, we might then expect peace (the result of reconciliation) to have similar importance. It is striking that in all his letters, Paul modifies the tradition greeting from ‘grace’ to ‘grace and peace.’ Michael Gorman thinks this is no accident:

For Paul, the prophetically promised age of eschatological, messianic peace has arrived in the death and resurrection of Jesus the Messiah, an age characterized especially by reconciliation and nonviolence.

Alan Spence, in his fascinating study of the atonement in Paul, also puts peace at the centre of Paul’s theology:

[I] offer a provisional, highly condensed answer to the question: Why did God become man? It takes the shape of a master-story, presenting in narrative form the concept that Jesus is Mediator: The Son became as we are so that he might, on our behalf, make peace with God. This is more than an account individual forgiveness. It summarises God’s gracious intention to reorder and reconstitute around himself the broken relationships of his suffering and alienated creation through the death of his Son and by the work of his Spirit.

This perspective must fundamentally affect the way we view violent conflict as a way of resolving differences.

This first appeared on Ian Paul's blog, Psephizo, and we are grateful for permission to reproduce it here.