1 Daffodils

Years ago, I visited the home of art scholar and historian Nicolete Gray. In her bedroom, next to her bed, was a watercolour of dying daffodils in a glass vase. The vase, water and flowers were nearly translucent, difficult to see, the petals shrivelling and stems breaking. I couldn’t see why you would want such a barely visible, gloomy subject – flowers fading and fit to be thrown out.

Just as I had reached this conclusion, however, a beam of sunlight came through the window and glanced on the painting, and suddenly, a brilliant spear of gold light shot out from the fading petals. From deep within the layers of watercolour, the lost life of the daffodils radiated blindingly and so transformed the painting into a riot of moving colour that I took a step back, speechless. Nicolete looked at me and said, ‘you understand then, why an ageing lady might find this...hopeful’.

The painting was by the artist and writer David Jones (1895-1974), and the brilliant gold shining of the flowers, emerging from the layered watercolour explains why reproductions of his paintings never do them justice, particularly his religious inscriptions, where gold letters often flame out from the calligraphy. His works are interactive, - they demand you wait for their story; they tell you different things at different times in different lights and they are there to reveal to you the doxa, the deep, shining life, the inscape, of the glory of God.

There has recently been renewed interest in David Jones as a Christian artist and writer, particularly since the publication of a comprehensive bibliography by Thomas Dilworth - David Jones: Engraver, Soldier, Painter, Poet (Jonathan Cape 2017). I came to study David Jones through his poetry, given to me by a tutor who wanted to educate me in ‘resistant’ texts. I had already ‘done’ the usual war poets, and she suggested I tackle Jones’ In Parenthesis, his great meditation on his experiences of the First World War, which left him wounded in Mametz Wood and haunted him for the rest of his life. ‘You won’t have any idea what’s going on’ she said loftily, and she was right. So I read the rest of his work, including the terrifyingly complex and dense Anathémata. I didn’t understand any of that either. But the poetry was so beautiful, so urgent; it got inside my head and my heart. I heard his comrades marching in my dreams, I felt King Arthur turn over in his sleep, I heard songs and hymns and found myself in chapels and churches, the bread and wine laid out, the priest raising the host and proclaiming the Lamb of God, over and over again. And David Jones himself warning, in a poem called A, a, a, Domine Deus:

I have been on my guard

not to condemn the unfamiliar.

For it is easy to miss Him

at the turn of a civilisation

2 The Grail

I excavated him first in those trenches of the First World War. Like Isaac Rosenberg, but unlike some of the more well-known officer-poets, he was a plain Tommy, and an artist with an artist’s eye, cataloguing details of the horror of trench life. They leak out in In Parenthesis, the barbed wire, the cold, the sharp rasp of cigarette smoke in the mouth, the songs, the swearing, the gas, the death, the terrible death. It was a place of rats and horror, and powerful, enduring friendship. And an epiphany; a blazing experience of God’s love.

One night as he was looking for firewood, David Jones, then nominally an Anglican, happened upon a Roman Catholic priest saying Mass in a shed among all the destruction. Looking in through a crack in the planks, he saw candles and vestments and tough old sweats kneeling and receiving Christ (Dilworth, pp. 47-48). David Jones was steeped in the Arthurian legends and went around with a copy of Malory’s Morte D’Arthur in his pocket and at that moment, he knew exactly what it was to be Lancelot, glimpsing the Holy Grail, knowing what it was, but too sinful to reach it, yet desiring it with all his heart. It was perhaps then that Jones realised the power of a visual scene on an observer and also how the power of poetry could prompt and nurture personal encounter with the Living God. He spent the rest of his life, wracked with what today we would call PTSD, trying to recreate that life-changing experience for his friends, readers, viewers. Having found Christ in that darkest of places, he would want that revelation for everyone. Sometime later, he became a Roman Catholic and threw himself into exploring what that decision meant.

His greatest theological mentors were Maurice de la Taille, whose Mysterium Fidei offered the closest account of what he had seen and felt that day in the trenches, and Jacques Maritain on the relationship between art and sacrament, on which Jones wrote and re-wrote. But he read voraciously in all kinds of genre, and everything he read, the Mabinogion, Jessie Weston, Spengler’s Decline of the West, Frazer’s Golden Bough, Mircea Eliade, he soaked up and added up to a giant mythos of human desire and desperate longing for the divine.

All of that reading spills out into the poetry which needs translation for bits of Greek, Latin and Welsh, and complex annotation to make sense of his deep erudition. To follow him, I made it my business to read everything I could determine he had read, tracking down obscure phrases and references to find out where they came from, to think as he had thought. I remember a Eureka moment, when, puzzling over a missing link in his personal mythology, I came across an old, old book, mouldering away in a forgotten corner of a library which contained some extra verses of the old folksong, John Barleycorn and from which he had quoted. I had literary maps stuck on the walls, and fiercely scribbled-on reproductions of his paintings and inscriptions. I trawled the Scriptures endlessly. And I discovered that for him 1 Peter 1.20 means that all pre-Christian religion and mythology were still shot through by God’s call to love and know Christ: ‘Nor bid Anubis haste, but rather stay:/for he was whelped but to discern a lord’s body’. There is no place in time or space, no muddy trench so deep, where God does not send his saving love in Christ. John Barleycorn, cut down but springing up again, is yet another type of Christ, filling people’s minds with the mystery and glory of Jesus’s death and resurrection, even if they could not name it.

3 Turn to Christ!

So: suppose you could write a poem which drew the reader so deeply into its spiritual complexity, its blazing truth and glorious beauty that the reader experienced Jesus dying and rising, and surfaced from the poem realising that she had been attendant at a Eucharist, and received God present in bread and wine? Now your poem is not just a poem but a form of outreach, convincing through the power of words, evangelism by aesthetics, the irresistible beauty of Christ found in worship.

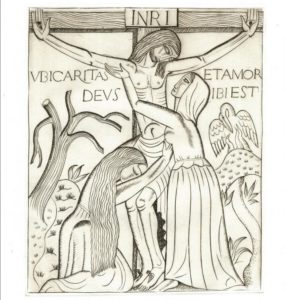

The Crucifixion, Copper Engraving

Ambitious? Impossible? Many literary critics have been completely bamboozled by David Jones’s writing, famously dense, layered, dazzlingly complex, arcanely theological, precisely because its underlying desire is to make you see what he sees and what he has experienced: powerful, life-twisting encounter with the Living God. But in David Jones this urge to find the beauty of holiness was neither effete nor saintly; there is in all his work the grinding pain of the human condition and of serious, filthy, back-breaking work. At Ditchling, alongside Eric Gill, he learned through toil how to carve, engrave and inscribe. And, more urgent than this, he was aware of Christian faith slipping away, becoming less central in people’s lives, replaced by technology, relativism, indifference. He kept the words hora novissima, tempora pessima sunt: vigilemus over his bed. 1These words are the opening lines of the poem De Contemptu Mundi (On Contempt for the World) by the 12th century monk, Bernard of Cluny: 'These are the last days, the worst of times. Let us keep watch' . They are best known in J M Neale's translation as a hymn: 'The world is very evil,/The times are waxing late; /Be sober and keep vigil,/The Judge is at the gate'. Briefly engaged to Gill’s daughter, Petra, he never married.

Peter Levi SJ, classical scholar, poet and friend of David Jones summed him up at his Requiem in Westminster cathedral: ‘David Jones had a devoted, suffering life. He was full of gaiety and sweetness throughout many years of physical and mental illness. He was the friendliest and most loving of human beings and he was terribly lonely. ...yet he was possessed continually by the drifting light of an unexplained hope’.

It is that hope I found in those dead daffodils, and in the poetry. And yet, again and again, David Jones brings us back to Jesus Christ. The last words of the Anathémata are direct questions to the reader: demanding we say ‘yes!’ to God’s offer of saving love.

What did he do other

recumbent at the garnished supper?

What did he do yet other

riding the Axile Tree?

Dr Anne Richards is the Church of England’s National Adviser on Mission Theology, New Religious Movements and alternative spiritualities. Before that she read, and taught, English at Oxford University, specialising in modern and religious literature. She wrote her doctoral thesis, under Peter Levi, on David Jones. She is the convener of the ecumenical Mission Theology Advisory Group (MTAG) which provides mission resources to the churches (with a particular interest in equipping Christians to share faith effectively and in understanding the spiritual lives of people outside the Christian faith as seen in publications such as Sense Making Faith (2007) and Unreconciled? (2011)) and the content manager of www.spiritualjourneys.org.uk for spiritual enquirers and www.dispossessionproject.org on ways to explore mission and social justice.

References

| ↑1 | These words are the opening lines of the poem De Contemptu Mundi (On Contempt for the World) by the 12th century monk, Bernard of Cluny: 'These are the last days, the worst of times. Let us keep watch' . They are best known in J M Neale's translation as a hymn: 'The world is very evil,/The times are waxing late; /Be sober and keep vigil,/The Judge is at the gate'. |

|---|